The NBA On NBC Partnership: The Relationship changed sports media and crowned the NBA," John Kosner's latest SBJ column with Ed Desser

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, by John Kosner and Ed Desser, September 19th, 2022

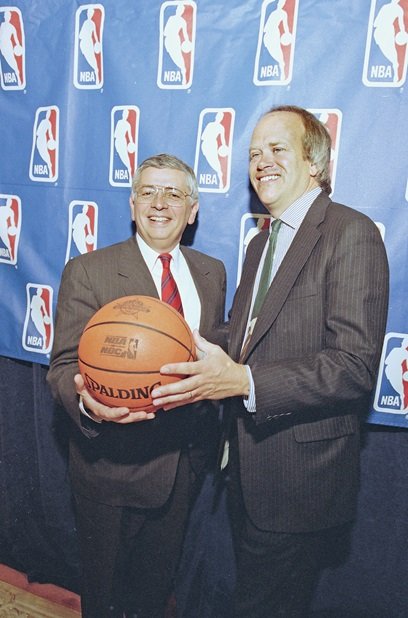

NBA Commissioner David Stern and NBC’s Dick Ebersol worked together to greatly expand the league’s coverage.

AP IMAGES

“A spectacular move!” Sports fans know the clip — Michael Jordan switching hands in mid-air to score; the call from the legendary Marv Albert. But we’re writing about another, similarly spectacular move made by the and NBC on Nov. 9, 1989:

NBC stunned the industry 33 years ago by paying the NBA $600 million-plus, more than triple what the incumbent had been paying, putting the NBA on the map, cementing the visionary reputations of NBA Commissioner David Stern and NBC Sports President Dick Ebersol as sports impresarios, and birthing a truly unique league/network “marriage” that netted (pun intended) a massive “win-win.” It represented a pivotal moment in our careers, and reordered sports media, transforming the NBA.

First, the context: Ed joined the NBA in 1982 as its director of broadcasting/executive producer; John started out as programming assistant at CBS Sports. That season, CBS scheduled only five regular-season NBA games — each involving the Lakers, Celtics and 76ers. Until 1982, weeknight NBA Finals were on CBS late-night tape-delay, so concerned was CBS not to air NBA games in prime time during the crucial “May Sweeps.” The NBA was a programming stepchild. “Our fans like us,” Stern once mused to John, “but they don’t like themselves for liking us!”

The NBA began to rally in its final years with CBS, as Ted Shaker took over as executive producer, adding innovations like “At the Half with Pat O’Brien” and slicker productions that highlighted the many emerging NBA superstars, like Jordan. Just after 6 p.m. ET on Sunday, May 7, 1989, Jordan electrified the nation, hitting the hanging, series-deciding, buzzer-beater over the Cavs’ Craig Ehlo in the opening round of the playoffs. We took note.

We were now working together at the NBA. CBS itself shocked the industry (and us) by paying $1.1 billion to take away NBC’s 41-year national TV “birthright,” providing NBC with airtime and motivation, and us an opportunity.

The rise of Michael Jordan, shown here after winning the 1991 title, further added buzz around the NBA and NBC’s coverage.

GETTY IMAGES

With the NBA’s TV agreements expiring, we set out to -ize the NBA so that it could become the premium network sports property after football season. Rather than accept a network-centric new agreement, we drafted our own form, specifying key required elements — “the stuff.” We wanted weekly Sunday doubleheaders, “major sports” level of production equipment and an actual pregame show “in a studio,” not in front of a wall of monitors or a temporary set in the stands, as CBS had resorted to for budgetary reasons. And we wanted substantial on-air promotion, and cross-promotion between network and cable partners, to expand audience awareness of the NBA. “We willingly promoted games that were airing on, even though it was unheard of at the time,” Ebersol notes in his new book. Our goal made it very hard to stay with CBS, which had the NCAA Tournament, PGA Tour, and now MLB. And, perhaps most importantly, CBS didn’t see the NBA as we … or Dick Ebersol did.

“Within 48 hours of when I started the job at NBC Sports, I went to … meet with David. We hit it off from that point,” Ebersol recalled recently. “Prime time was what we were selling — not just for the Finals or later rounds of the playoffs, but finding ways of getting Sundays into prime time.” Of course, Ebersol and Stern recognized the Jordan/Ehlo effect too.

Ebersol is on the Mount Rushmore pantheon of sports legends, along with his mentor, Roone Arledge, and Stern. What distinguished Ebersol and Stern was that not only did they think big — they did big. That summer, Ebersol (who ultimately served as NBC’s chief executive, programmer, and executive producer for the NBA on NBC) traveled to D.C. to meet with FCC reps — the topic: Could a sports program that contained educational content qualify for the mandated Saturday morning Network TV kids block? The answer wasn’t “no.” Ebersol’s legwork begat “NBA Inside Stuff,” a weekly program produced by NBA Entertainment that ran midday on NBC just prior to live sports every Saturday for 12 years, indoctrinating generations of young adults to the NBA.

So strong was the partnership between Ebersol and Stern, and their respective standings so high with their employers, that Albert’s trademark “Yes!” became the default response when the league or network asked something of the other. As Ebersol said in his book, “the partner always came first.”

Links to NBC / NBA video clips:

John “Tesh Roundball Rock”

NBC’s signoff (all the great moments)

An “NBA Showtime” pregame show from the first season

In a novel move, NBC provided the NBA with a $10 million/year bank of prime-time promotion, which led to the “I Love This Game” campaign. A dozen-plus executives, production people, marketers and ad sellers from both sides gathered weekly for lunch, forged relationships and created great value together. They were afraid not to because Ebersol and Stern made cooperation and success an imperative. “Meetings like that had never happened before in any partnership between a league and network,” Ebersol said. The evocative “joint logo” was emblematic of the parties’ collaborative, integrated spirit.

One star was Jim Burnette, head of NBC Sports sales. Burnette knew the NBA was particularly strong in the second quarter, which was heavy auto sales season. He boldly expanded CBS’s previous two NBA-exclusive auto advertisers to eight, each getting one-quarter of exclusivity and four units every other game. And he moved fast. At the 1990 Super Bowl, Burnette successfully made the pitch, getting seven autos (including GM, which bought two eighths). He also lined up McDonald’s as the halftime sponsor, locking in revenue of hundreds of millions in just a couple of months. Shortly thereafter, the economy collapsed. CBS’s first World Series was a competitive and financial bust (a four-game sweep). But the NBA on NBC was already on a solid financial launchpad.

Two years later, when the NBA and NBC extended their already hugely successful agreement early, the parties added an ad revenue share. That heralded an unprecedented amount of information-sharing and created a practically unheard-of fertile environment, where the league was actively seeking advertisers for its network partners and vice versa.

Eight years after the NBA on CBS had scheduled a five-game regular-season slate, NBC aired 26 games featuring 14 teams. Now there was a legitimate pregame show, “NBA Showtime,” superbly hosted by Bob Costas, and the doubleheader games voiced by play-by-play legends Albert and Dick Enberg. The sidelines were patrolled by Ahmad Rashad, who initially bristled at Albert’s tag, “The Dean of Sideline Reporters,” until he realized that fans liked it. The first NBC analyst, Mike Fratello, was similarly dubbed, “The Czar of the Telestrator.” John Tesh wrote the score, “Roundball Rock.” It was a show, and it was fun.

Whereas CBS was often plagued with local station preemptions, Ebersol had NBC affiliate relations offer the NBA schedule as an “all or nothing” block. The stations had little choice and the NBA had 99%-plus distribution. This helped ratings, as did Ebersol’s understanding of Nielsen. By forgoing a pre-tip break, Nielsen would start the national rating during live action, and the closer the last spot ran to the end of the game, the higher the game’s average. In its first season, NBC was also rewarded with a dream Chicago-L.A. Lakers final, an actual changing of the guard from to Michael, and a ratings hit.

NBC offered the prime-time exposure, and shoulder programming, the NBA needed to boost fandom.

GETTY IMAGES

In late April 1992, the Rodney King riots gripped L.A., scrambling the playoff schedule. Working together with the NBA’s longtime schedule maker Matt Winick, we imagined an opportunity. With three games on Sunday, May 9, but only a doubleheader booked for NBC, what if … we could convince NBC to go at 12:30, 3:00 and 5:30 p.m. ET — the first NBA network tripleheader, climaxing with a must-watch game: the champion Bulls with Jordan at the Knicks with Patrick Ewing and coach Pat Riley. Going nearly unopposed 5:30-8 p.m. ET on Sunday wasn’t possible at CBS (“60 Minutes” was untouchable). But we got to “Yes!” quickly, also by borrowing another NFL innovation: offering the local NBC stations a halftime news break to make up for the news preemption. That night, the Knicks shocked the Bulls, providing a powerful NBC prime-time lead-in during the May sweeps. From then on, tripleheaders and the late Sunday window became the norm for the NBA on NBC, many distinguished by remarkable performances from Jordan.

Stern taught us to understand and strategically use our “assets.” The 1992 Olympics Team is a great example. The USA team had to qualify for Barcelona. The NBA and NBC staged and marketed their “Beatles-like” Dream Team debut. At the Olympics, Ebersol opened prime time with Dream Team games, introducing huge audiences to stars like Karl Malone, David Robinson and Charles Barkley — not to mention Larry Bird, Magic and Jordan, captivating the world and catapulting the NBA to an even higher orbit.

“I miss David every day of my life. He was a … stimulator in my life and a great, loyal friend,” said Ebersol last month. Stern would have said the same, especially if the NBA retained the 5:30-8 p.m. ET time slot and a share of ad revenue!

Today, Ed Desser (www.desser.tv) and John Kosner (www.kosnermedia.com) each operate sports media consulting businesses. They collectively served three decades as the senior media executives at the NBA, collaborating during the heyday of the NBA on NBC.

"Make Media & Tech Innovations Work for You," John Kosner's latest SBJ column with Ed Desser

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, by Ed Desser and John Kosner, August 29th, 2022

You ain’t seen nothin’ yet!

That’s our feeling about sports media. As you try to follow the accelerating changes, we’re here to help. Our suggestion: Follow the Tech. We see nine key innovations changing our industry this decade:

Real-time information: The power of sports is that it’s live and its intrinsic appeal cuts across all demographics, getting everyone simultaneously focused on a single event. Yet, we’re just scratching the surface. You’re typically streaming 45 seconds behind live action. Trying to find a game? Good luck! Powerful solutions are coming — score fixes for your phone and wearables, sub-second latency streaming, and the race is on to provide the 21st century sports “TV Guide.” No more sports fan FOMO! Instant custom curation of live events, triggering tune-in for start of games, significant in-game reporting, social interaction, sharing of remarkable plays and propagation of data to drive gambling.

The cloud: It’s fashionable to deride personalization as an overhyped pipe dream. But the ascension of giant cloud companies and privacy-protection software will enable sports properties with significant data to join forces, unlocking the ability to truly know their fans, creating huge value. And for fans, finally, the opportunity to get value from that shared knowledge such as combined packages of streaming, tickets, merchandise and exclusive team/player access. But cloud innovations extend well beyond that. Today, game telecasts can be directed on an iPad and voiced from any location on the globe with a high-speed connection.

Games: Growing up, TV was our default. Now, playing games is mainstream — as an activity and a business. In the past five years, viewing of esports and game streamers has exploded on Twitch and YouTube, transforming spectators into participants. See the effects in traditional sports game presentation (EA’s Madden has meaningfully influenced NFL coverage with Skycam for NFL telecasts). Today’s carefully produced live-event megacasts will soon be supplemented by platforms giving everyone a voice. Here, podcasting presents a true launching pad. Example: JJ Redick on ESPN. League video game rights may rival broadcast fees (see FIFA’s next agreement following its 30-year partnership with EA).

Betting: Consolidation in sports betting will trim today’s dozen players into a big 3-4, and the reality of sports’ “big bet” on gambling will play out. Betting advertising will become national too. Other effects are uncertain. Through aggressive industry marketing, some fans are already more interested in their fantasy players or action on a particular game rather than “their” team. We foresee increasing friction over vague “official” injury reports. In-action wagering, powered by sub-second latency streaming, is also coming. Look for MVPDs to embrace “live live” sports as a rationale to stay subscribed to the endangered TV bundle. All of this will challenge the unified fabric that’s traditionally made sports, sports.

Artificial intelligence: Startups mastering computer vision (“Shazam for Video”) are revolutionizing everything from content algorithms to sports video highlights, social media monitoring, athlete scouting and combating streaming piracy. Astonishingly, most of these breakthroughs will be invisible to fans. Fans will find themselves watching more TikToks, not sure why, but noticing more, better and increasingly tailored services. The combination of relevant AI data and cloud breakthroughs will further accelerate development of new sports products and services.

Networks for everyone: As audiences continue fragmenting, today’s social media networks will simply be “networks,” proliferating especially among elusive younger fans. The dominant social media experience at the 2028 L.A. Olympics has probably not even been created yet! Rights holders will have to work much harder just to identify and engage their audiences. Networks have already established virtual sports bars for fans to gather and express fandom, promote content and events, allowing players and teams to directly communicate, an on-ramp to …

The metaverse: At the height of COVID, 300 million people attended 2D interactive meetings on Zoom — building blocks of the metaverse, where people go to do things together. As Everblue’s games expert Dylan Glendinning explains: “A place where your digital identity is just as important as your physical identity.” Our former colleague Steve Hellmuth points out the significant role of key NBA partner Microsoft. It hosts sports and games (Xbox, Halo and soon, presumably, Activision), and it’s a leading funder of the metaverse, making virtual workplaces productive (270 million active “Teams” monthly). Expect the creation of new 3D interactive services as sports and games experiences merge.

Premium streaming: We expect streaming’s superior user experience to continue slowly decimating the traditional TV bundle. From a business standpoint, it’s a mixed bag. Streaming allows content owners to go direct, eliminates the need for middlemen, creates many new bidders for rights, allows for wide variety of new offerings and has created an exciting market in sports docs. AppleTV+, Prime Video, FloSports, ESPN+, Paramount+ and Peacock each expand demand for live sports while simultaneously attacking the bundle (where the money still is), spreading audiences thinner. In addition, for the most popular games, streaming millions of feeds is inherently inefficient versus traditional multicasting. The challenge, regardless, will be getting young fans to pay considering that …

Free streaming is also exploding. Not just YouTube, Twitch, Snap, Instagram, Twitter, but also the doppelganger FAST services (free ad-supported streaming) being launched by all top pay TV networks, the vast competition for time and attention from user-generated interactions detailed above, and pay TV piracy.

There is no clean, well-lit path ahead. Our best intelligence is to improve your product by making these and other technical innovations work for you.

Ed Desser is an industry expert witness and president of Desser Media Inc. (www.desser.tv), which has advised on over $30 billion in sports/media transactions. John Kosner is president of Kosner Media (www.kosnermedia.com), a digital media expert and sports startup investor. Together they developed league strategy and ran the NBA’s electronic media operation in the 1980s and ’90s.

Questions about OPED guidelines or letters to the editor? Email editor Jake Kyler at jkyler@sportsbusinessjournal.com

John Kosner spoke with Ben Mathis-Lilley, author of “The Hot Seat: A Year of Outrage, Pride, and Occasional Games of College Football,” for the NY Times.

Original Article: The New York Times by Ben Mathis-Lilley, August 27th, 2022

It is, let’s say, 8:43 p.m. on a Saturday. You are watching a college football game that is taking place at this hour despite being played in the Midwest in November, and the people in the stadium, which is not entirely full, look very cold and a little put off. The season schedule said kickoff was at 8 p.m., but it didn’t actually take place until 8:18. In the 25 minutes that have elapsed, play has been interrupted for three commercial breaks. Each advertisement shown during these breaks has been for pickup trucks.

The announcers have just begun a discussion of your team’s head coach, and his alleged inability to win “big games,” which is indistinguishable from identical discussions held by other announcers in each of the team’s nine previous contests.

You will continue watching this broadcast until it ends at 11:47.

Why? Because you are a college football aficionado and the bond between you and the team you support is an idiosyncratic one that is hard to extinguish.

In an era in which television ratings are in decline, the aggregate live-audience demand to which you contribute — some teams can bring in more than three million viewers every week, on average — is valuable for the multinational corporation broadcasting the game. This demand lasts through the season, which begins for most teams this weekend and runs through, if you are lucky, January of next year. It is not necessarily affected by the quality and care with which the broadcast has been produced.

You are a case study in the consolidation of modern media: It can still be hugely lucrative to provide you with an experience that, in many respects, you find insulting.

As both a professional journalist and an expert on watching college football, I felt obligated to explore such matters while researching my forthcoming book “The Hot Seat,” from which this article is adapted. The book tells the story of overenthusiastic modern college football fandom through the 2021 Michigan Wolverines (average weekly viewership: 4.74 million) and their divisive coach, Jim Harbaugh. I took my responsibilities so seriously that I often asked my wife to mind our three children during the team’s games so I could observe and consider the state of televised sports with the clearest possible mind. (She often declined.)

I also spoke about the subject with John Kosner, a former ESPN executive who helped oversee college sports at the network in his 21 years at the company, owned by Disney, and now runs his own sports media business. Mr. Kosner grew up in New York and became a fan of college football because it was, in his words, “so different from anything I experienced.”

But what college football is now is far from what he first started watching regularly in the 1970s. There is much more of it on television, for one thing. And each school and conference wants, understandably, to maximize its earning potential in a competitive environment. (A 1984 Supreme Court ruling forbade the N.C.A.A. from single-handedly controlling its members’ TV rights.) It’s an arms race of commercial breaks.

“You’re making deals at the demand of these conferences and of the media companies you work for and it’s a competitive arena,” Mr. Kosner said. “You might decide, ‘Gee, this is terrible. We shouldn’t do this.’ But if you decide not to make a deal, someone else is going to make that deal.”

This is true. Big Ten games have been broadcast on ESPN and ABC for years, but the parties were unable to come to terms on a renewal of their relationship. The seven-year, $7 billion agreement the conference announced this month is with Fox, CBS and NBC instead. Disney still dominates college football, having televised 41 of 2021’s 44 postseason bowl games. In 2020, it secured exclusive future rights to broadcast the Southeastern Conference, whose teams are more successful on the field than the Big Ten’s and almost as popular.

“What happens is the conference is saying, ‘OK, we want more for our rights, or we want $25 million for the championship game,’” Mr. Kosner said. “And the answer frequently is, ‘We want to expand the commercial for that.’ And they say, ‘OK.’” In response to questions about how long games now take — up to four hours with all the scheduled breaks — and whether this tangibly affects the live experience, an ESPN spokeswoman noted that many factors affect the length of a game, including the style of play, replay reviews and advertising.

“Commercial breaks are a standard part of every televised sport and are a major element of media companies recouping their significant investment,” the spokeswoman said. Michigan’s 2021 season was unexpectedly redemptive, but in the years prior the team’s supporters were subject to relentless, hurtful reminders on game broadcasts that, as head coach, Mr. Harbaugh had never beaten Ohio State, had a poor record against elite teams in general, and had failed to win a Big Ten championship. A Tampa-based sports TV expert, former Deadspin editor and archivist named Timothy Burke helped me compile transcripts of 43 Michigan football broadcasts aired between 2018 and 2021; there were at least 31 comments about Mr. Harbaugh’s not having beaten Ohio State in the file, and I excluded the actual games against Ohio State from my search.

Coach Harbaugh’s purported overratedness was a favorite subject not just during games but also on ESPN’s original programming. One of the network’s college football pundits, Paul Finebaum, has described him as “the most overpaid coach in college football history,” “stunningly embarrassing,” “an idiot,” “a colossal failure” and “a total fraud.” As Mr. Finebaum noted with enthusiasm, until last season, Michigan had never made the College Football Playoff — the four-team championship system that began in 2014, to which ESPN has exclusive TV rights.

Mr. Finebaum wasn’t the only person on ESPN from whom one heard about teams that had succeeded or failed by making or not making the College Football Playoff on ESPN. According to an article in The Athletic, the C.F.P. was mentioned 27 times during one three-hour December 2020 episode of “College GameDay,” the network’s flagship news and discussion show for the sport. Nine promos for the Playoff ran during a 2021 bowl game I happened to watch. (Fine: It was the Cheez-It Bowl. I watched the entire Cheez-It Bowl.)

But what recourse do fans have? ESPN is increasingly the only game in town, which reflects the hollowing out and nationalization of the media more broadly.

Daily newspaper circulation in the United States has fallen to 24 million from 62 million in the past 50 years, according to the Pew Research Center. There were about 80,000 newsroom employees in the country combined between newspapers and the internet in 2008, according to Pew, and by 2020, that number fell to 49,000.

In the athletic realm, Sports Illustrated has been controlled since 2019 by a company that has variously called itself TheMaven, Maven and The Arena Group, and whose central project as owner of the magazine seems to have been to attach its brand name to team-specific sites run by individuals who don’t necessarily have journalism training. (“College football is on fast approach,” begins a recent post on one of those sites.)

ESPN, for its part, employs some of the best reporters and commentators in the industry, but is cutting them at an alarming rate. About 100 newsroom contributors were terminated in a single day in 2017, and more were dropped during the pandemic. One way ESPN fills its schedule now is with so-called hot takes: This is the five hours of weekday broadcasts filled with talking heads — opinionated journalists and ex-players — airing their hyperbolic and provocative views.

Fox Sports — which is part of the Murdoch-controlled Fox Corporation — is nominally a competitor of ESPN’s, but it may be more accurately described as an imitator. About five years ago, the company laid off nearly all its writers and reporters and hired away a number of ESPN talking heads and the top producer of ESPN’s talk shows. Fox’s lineup can feature six daily hours of the discussion (i.e. argument) format.

One of the top ESPN-to-Fox personalities is a longtime radio host named Colin Cowherd, who once noted, in an almost admirably honest interview with Bryan Curtis of The Ringer, that “in my business, being absolutely, absurdly wrong occasionally is a wonderful thing.” He also said he constantly tells one of his friends in the industry that “there’s no money in right,” and concluded a rumination about whether he’d been wrong about the subject of that day’s show — his accusation that a particular quarterback didn’t prepare enough for games — by asking, “Who cares?”

Wrong on purpose is not necessarily a bad strategy. Opinion stories are disproportionately represented at the top of news sites’ most-shared lists, and internal Facebook memos made public in the fall of 2021 revealed that the company had been rewarding outside content that users reacted to with the “angry face” emoji with better placement in news feeds. Executives and producers further emphasize characters and story lines they believe will be especially divisive: Tim Tebow, LeBron James and whether he chokes or is better than Michael Jordan, the Dallas Cowboys in general, and so on. “I was told specifically, ‘You can’t talk enough Tebow,’” the pundit Doug Gottlieb said after leaving ESPN in 2012.

Disney knows the value of a captive, excitable audience — in addition to its sports rights, it owns the Star Wars universe, Marvel comic book characters and Pixar, among other things. Disney’s profits jumped 50 percent in 2021. The financial information firm S&P Global Market Intelligence estimates that ESPN makes more than $8 a month from each of its nearly 100 million cable subscribers; it estimates that the most lucrative cable channel that doesn’t show sporting events, Fox News, makes about $2. There are 16 scheduled commercial breaks in national college football broadcasts, which can last as long as four minutes each.

Curious as to whether this feeling of oppression by a cultural monopoly might be addressed by the kind of legal remedies more typically associated with companies that make steel beams and computer software, I spoke to a University of Michigan law professor and antitrust expert named Daniel Crane.

He was open to the idea that my lengthy complaints about commercials and hot takes were evidence of “quality degradation,” that being one of the typical consequences for consumers of a monopolistic market. (The others are rising prices, diminished innovation and reduced output. Mr. Crane, for the record, says that if he’s not at a Michigan game in person he usually listens on the radio.)

But he cautioned that simply being a monopoly doesn’t mean anything has to change. “Unless you can show that they have obtained or maintained their monopoly through anticompetitive means,” he said — and despite the allegations mentioned above, no litigant or regulator has formally done that — “it’s just kind of too bad. ”

What’s more, he added, the law doesn’t really care that to fans of a particular team, changing the channel to watch another game isn’t the same as switching to a different brand of dish soap.

Reporting which preceded the Big Ten’s recent contract suggested that college administrators had themselves become uneasy with the amount of control that ESPN and Disney had over their sport. Whether this will ameliorate the quality degradation remains to be seen. Certainly none of the news releases about the deal that I have read mentioned anything about reducing the duration of commercial breaks.

Is this a silly thing to worry about? Yes and no. On the one hand, college football is not as materially crucial of an issue as, to take two examples, climate change and cancer. On the other, like all cultural narratives, highbrow and low, it has an intangible but foundational importance to the lives of those who use it to define their social communities and to explain their personal origins and values — to understand how life works, basically.

Karl Marx held that alienation is the condition people experience when they have no autonomy over something personally or socially meaningful to them because it is subject to the power and incentives of accumulated capital. I believe I embody the concept, as so defined by Marx, when I am watching five to eight consecutive commercials 16 times during a college football broadcast so that Disney shareholders and Rupert Murdoch might benefit.

Mr. Crane’s advice to unhappy viewers, informed by the success that European soccer fans had in killing a consolidated “Super League” proposal in 2021 by exerting pressure through political channels, was to pursue activism at the local level — to create a headache for university presidents, regents and others who actually have the leverage to tell a TV network to cool it.

But what makes the situation tricky is that fans have an incentive to want their schools to sell out too. The essence of college football’s hold on its audience is that it asserts a particular school, state or region’s status and relevance in a way that no other activity, even any other sport, can.

To choose not to have the financial resources other schools might be availing themselves of, to walk away from the prime-time slot, would be contrary to the entire enterprise. I do a great deal of whining about announcers, but when Fox analyst Joel Klatt said (to Colin Cowherd!) that the atmosphere during Michigan’s 2021 win over Ohio State in Ann Arbor was “the best environment I’ve ever been at, in any sport,” I was proud. Thanks, Joel!

When I spoke with Mr. Kosner, the former ESPN executive, he recounted the stakes of a Thanksgiving 1971 game between Nebraska and Oklahoma that he remembered watching. “It had everything,” he said. “It was everything you would imagine from middle of the country, a super-rivalry between states.” (I think he is right that a football game between Oklahoma and Nebraska would have been the exact conceptual opposite of 1970s New York City.) “That game doesn’t happen anymore because Nebraska chose to go to the Big Ten,” he said wistfully.

Of course, as he recognized, the reason Nebraska joined the Big Ten was so it could reap the rewards of consolidating its brand with those of other national draws like Michigan, Ohio State and Penn State. That choice was offered to the school by executives like John Kosner, and was accepted enthusiastically. Nebraska averaged 2.29 million viewers a week last season, and there’s no going back.

John Kosner spoke with Jon Wilner of Pac-12 Hotline about Conference TV negotiations

Original Article: The Mercury News, by Jon Wilner, July 20th, 2022

The Pac-12 lost its marquee football and basketball programs, its biggest media market and the links to its main recruiting pipeline three frenetic weeks ago. Since USC and UCLA made their flight plans known, the conference has been portrayed as everything from fragile and fractured to a carcass on the savanna awaiting vultures from the Big Ten and Big 12.

But the dire predictions seemingly overlook one important element as the conference negotiates a new media rights package: The Pac-12 offers ESPN something no other Power Five league can match.

A steady supply of night games.

“The beauty of the Pac-12 is you can program that late (Saturday) window for 13 consecutive weeks,’’ said John Kosner, a sports media consultant, president of Kosner Media and former executive vice president/digital media at ESPN. “It takes a conference to do that, because it’s hard for individual schools to play more than a handful of those games each season.

“Let’s say you get practically a 1.0 rating and 1.5 million homes on average per (night) game. That’s considerable audience delivery for 3.5 hours every Saturday. That’s very hard to replace. “It’s hard to take something away from somebody. The fact that the Pac-12 has been on ESPN for a long time — it’s part of the firmament there.” In a twist worthy of #Pac12AfterDark, the reviled night games could play a vital role in the conference’s survival.

Yes, Larry Scott got something right.

“Nobody else can fill those time zones,” said Ed Desser, the president of Desser Sports Media and former executive vice president for strategic planning/business development at the NBA. ESPN’s college football programming template features five windows: College GameDay at 8 a.m. (Eastern), followed by kickoffs at 12 p.m., 3:30 p.m., 8 p.m. (primetime on ABC) and late night.

While the late games (10 or 10:30 p.m.) lose audience when fans in the eastern half of the country go to bed, they still carry significant value for ESPN because of their unopposed nature — no other Power Five games are being played — and the 12-hour cross-promotional opportunities baked into earlier programming on ESPN.

That gives the Pac-12 an advantage over the reconfigured Big 12, which will have only one team (Brigham Young) in the western half of the country, home to 75 million people.

“I’d argue that if ESPN lost the Big Ten, it would have the Big 12, ACC and SEC games for the Eastern and Central time zones,” Kosner said. “But without the Pac-12, it doesn’t have the Mountain and Pacific time zones. “It can’t get those games any place else.”

One motivation for ESPN as it ponders a new contract with the Pac-12: affiliate fees.

The network generates immense revenue from the fees it charges distributors (DISH, Comcast, etc.) to carry its programming. Those distributors, in turn, need content that appeals to audiences in major media markets in order to drive monthly subscriptions. “College football is an important part of ESPN’s lineup,” Desser said. “Affiliate revenue doesn’t go up or down, it’s based on the programming you have acquired. ESPN has a bunch of affiliates on the West Coast, and having the Pac-12 goes a long way to making them happy.”

Not only is the Pac-12 unique among the Power Five in its ability to fill the late windows for ESPN’s affiliates, the local markets are substantial. The 10 remaining schools account for six of the nation’s top 30 media markets, according to Nielsen DMA data from 2021:

No. 6 Bay Area

No. 11 Phoenix

No. 12 Seattle

No. 16 Denver

No. 21 Portland

No. 30 Salt Lake City

“You cannot replace the ratings with the Mountain West,” Kosner said. “ESPN’s affiliates on the West Coast are used to having the Pac-12.”

There’s additional value for ESPN in a region of the conference you might not expect.

While Cal and Stanford have struggled on the field and don’t drive big ratings, they reside in a huge media market that includes Big Tech firms with executives who attended Pac-12 universities and follow the conference.

“The Bay Area audience is influential,” Kosner said. The late windows are so essential to the Pac-12’s media valuation that Kosner believes Thursday and Friday games “are prime opportunities” to explore with future network partners. Theoretically, commissioner George Kliavkoff could offer ESPN a premium matchup each Saturday night and a secondary game every Thursday or Friday, giving the conference at least 26 night broadcasts during the regular season.

With each window spanning 3.5 hours, that’s almost 100 hours of college football programming — much of it unopposed and supported by cross-promotion. “There are two types of valuations: marginal and intrinsic,” Desser said. “The Pac-12 has more intrinsic value because of those time slots.”

Under the current media contract with Fox and ESPN, each football broadcast is worth approximately $6 million to the Pac-12. The loss of the L.A. schools undoubtedly will impact valuation, but any decrease could be largely offset by market forces: The value of sports rights has soared since the Pac-12 signed its media deal 11 years ago.

“We haven’t done a valuation on the late window,” Kosner said. “But the fact is the Pac-12 can program for the late window without or without the L.A. schools, and it’s not like the L.A. schools have been the highest rated. Oregon and Washington have been.

“If you’re ESPN, you want the Pac-12 to hold together.”

"Why the Metaverse will be Epic," John Kosner's latest essay with J Moses

Original Article: Why the Metaverse Will be Epic, by John Kosner and J Moses, June 13th, 2022

Avatars from Blueberry Entertainment

It’s June, 2025 and we have tickets to the NBA Finals in Boston. Before we attend the game, we’re picking up one-of-a-kind outfits from Blueberry Entertainment. Yes, these outfits are actually for our avatars only (we have them for every game) … we’re attending the Finals in the NBA metaverse. And 19,580 fans will be there in person at TD Garden and the game will still be broadcast on network TV. But now there’s a new way to experience all of the action. NBA Commissioner Adam Silver has made the point that globally 99% of NBA fans never have the opportunity to see a game in person – now we are all another step closer. As is the connection between sports and games.

Peter Warman, the co-founder and now chairman of Newzoo, has fashioned the game’s version of “Moore’s Law” – namely that every five years since the breakthrough of online games in 2002, total engagement with games (measured by the number of people playing multiplied by hours spent) doubles. We’ll call that “Warman’s Law.” Over the past 20 years, we’ve seen unique accelerants like mobile and the free-to-play business model. The most-recent doubling to 1 trillion hours of engagement from 500 million has been driven by streaming of Esports and game streamers on Twitch, YouTube, and their Asian peers.

Warman makes the point that games and their developers put engagement first and believe money will follow. And it has. He estimates that in 2022, games will drive a stunning $203 billion in DTC (direct to consumer) purchases alone. That is larger than film, TV, and music combined and growing faster than all of them. Warman forecasts that the next double will be driven by the Metaverse and, within that, NFTs (non-fungible tokens) and P2E (play-to-earn) games – introducing ownership and authenticity to digital, making it easier to integrate with the “real” world.

Warman also has a measured definition of the Metaverse that we agree with: “a place people go to engage in any way or combination of ways they desire, together with others.” Games biz whiz Dylan Glendinning of Everblue Management, adds: “a place where your digital identity is just as important as your physical identity.”

We believe this is already happening.

Will the future of the metaverse be 3D interactive, virtual or augmented reality, all or none? Right now, we don’t think it matters. From a tech standpoint, the key to us is compatibility … and that’s why we think a game company is best situated to help fans begin to realize that potential. Game companies already allow players the most flexibility to express themselves in digital environments – not just to socialize, but to play games, flex for each other, even build actual businesses together.

When we were growing up, turning on the TV was the default leisure activity. Now, games are mainstream – both as an activity and a business. There are the games, the gamers (3.1 billion worldwide; half spending $11 per month on game content … talk about “RCS” – recurrent consumer spending!), the young audiences, game engines, and game developers. And, ascendant in youth culture per Warman’s stats, Esports.

There are a number of game companies with tremendous potential to build big businesses in the Metaverse … our focus today is Epic Games. They appear to have all the pieces – and a key differentiator, Unreal Engine (UE).

It starts of course with Epic’s existing metaverse, the online game Fortnite. Epic released Fortnite originally in 2017. It has become a global phenomenon, attracting 350 million players. Every day, gamers gather to play with friends and other players in the Fortnite metaverse. They own stuff. On the platform, they attend concerts, hang with celebrities, shop the Epic Games Store. It’s annually a $5 billion ecosystem with its own currency, V-Bucks, that can be bought with real-world funds, but also earned through successful activities within the games. In fact, Epic sells $3B of digital skins alone per year. Later this year, the Fortnite Esports tournament will return after a 3-year COVID hiatus.

Now imagine Fortnite gamers able to stroll around a much larger 3D metaverse. One that includes not just TD Garden but also SoFi Stadium, Wrigley Field, movie theatres, music clubs, and sports betting establishments. In their gear. With their friends. Packing their Fan Tokens. Able to use their V-Bucks to watch sports, concerts, or movies.

And, Epic has another huge advantage. It owns Unreal Engine, the game engine Epic uses to run Fortnite. It is a strategic asset. Games are notoriously expensive and difficult to create. Unreal is free-to-use for non-commercial use and levies a low royalty fee on big-budget games, saving thousands of developers millions of dollars of dev work. UE offers a full menu of products that can easily be purchased and integrated into any game; new development will enable the creation of NFT-based P2E games. Today, most popular games today are sitting on either Unreal or its competitor engine, Unity. Per Epic, 48% of next-gen console titles are being built on UE as well as eight titles that have generated over $1 billion. Here is what matters most: all of these games built on the Unreal platform have some form of compatibility and a partnership opportunity with each other.

This is critical because we believe the Metaverse will mirror today’s game business: walled gardens. And the key to success in the Metaverse will be compatibility or in the Web3 vernacular – “composability.” If you own stuff and currency in one metaverse, you’re going to want to take it to other metaverses. We might live in a decentralized future but a definitive advantage goes to the metaverse where the most people hang out – because that metaverse is going to be able to leverage the other metaverses, drive subscriptions, micropayments, etc. Discord plays that centralized decentralized role as a communications platform right now.

In addition to its 350 million Fortnite players and all of the new game development using UE, Epic is also building a war chest and mounting a challenge to Roblox and Minecraft in pursuit of time spent from young audiences. In April, Epic announced a $2 billion funding round, featuring additional investment from Sony and The Lego Group parent company KIRKBI. Including the new funding, Epic now has a valuation of $31.5 billion. Teaming Epic with the creators of both the Playstation and The Lego Group presents significant opportunities.

Of course, the competition too will be epic.

Meta, formerly known as Facebook, is single-mindedly focused on building the metaverse – in a way as Jack Dorsey observed that only a founder-led company can be. Meta is VR-centered as it has continued to build out its Meta Quest platform. But will our children choose Facebook as a metaverse hub vs. one created by a game company? We don’t think so. Games are the biggest entertainment category for Gen Z and Millennials and a close second (to music) with Gen X.

Microsoft could have an early edge. Not only will it host sports (key partner with the NBA) and games (Xbox, Halo, and soon, presumably, Activision) but it is among the major corporations funding the first iteration of the Metaverse, focused on making virtual workplaces productive, leading with its Teams product (270 million monthly active users). Microsoft is also a trusted brand. Note: Xbox and Unreal Engine have been partners now for 20 years. Within games, Roblox has more players compared to Fortnite, plus the ability for users to author content within their ecosystem. And Niantic, the Pokémon Go creator, raised $300M at a $9 billion valuation last November to build a metaverse based on augmented reality and the outside world. Niantic’s Lightship AR Developer Kit (ARDK) enables game developers to build AR games for free if they have a basic knowledge of the Unity game engine, the key UE competitor.

To Newzoo’s Warman, the Metaverse is nothing more than a natural evolution, pioneered by games two decades ago. We agree and see both sports and games as early winners. Sports because its large passionate audiences drive new experiences and businesses. And games because they will define the development of the Metaverse. On that front, Epic has a significant head start with Fortnite, a healthy balance sheet, strategic partnerships, and Unreal engine. But like the gauntlet run by the NBA Finalists, there’s a Murderers Row ahead with Meta, Microsoft, Niantic, Roblox, Riot, Take-Two, Sony, Steam, and the many, many others.

Game On!

This is the fifth in a series of essays about why games are ascendant in culture, especially among young people, and what those of us in Sports, Media, Investment … all of us in business … can learn from games. In our last installment, "The Adrenaline Economy" published in May 2021, we noted that Fans want action, involvement, real-time engagement. Entertainment options providing that electrical current are thriving; those that don’t are falling behind. We noted that one service with adrenaline is TikTok, "The World's Fastest Growing Game." We wrote that the massive virtual goods business in games worth $79B annually is coming to sports, finally, with the advent of “NFTs,” non-fungible tokens, "Is Gonzaga an NFT?" And we opined about how games naturally promote and benefit from super-engaged communities "A Trillion Hours! Why Community Is The Game Behind The Games."

John Kosner is President of Kosner Media (www.kosnermedia.com), a digital and media consultancy, and an investor and advisor in sports tech startups. He was the senior digital executive at ESPN for 15 years. J Moses has been in and around the Sports, Games, and Tech businesses for over 40 years. He has been a Director at T2 since 2007 and is currently an Executive Producer on a scripted Esports show for the CW (www.optinstudios.com).

On June 8, John Kosner moderated the Stanford University Class of '82 40th Reunion Panel: "Inside the World of Sports."

INSIDE THE WORLD OF SPORTS: This panel will feature classmates Andrew Brandt, Rod Gilmore, Fred Harman and John Kosner. Join us to hear how they pursued their passions after graduation and got involved in the business of sports. They will share their careers and experiences. Planned as an interactive conversation, we will open up the Zoom to discuss changes in the world of sports, starting with Stanfordthen moving on to events that are happening in the sports world in general.

“The Sports Streaming Evolution Halftime Report,” John Kosner’s Latest SBJ Column with Ed Desser

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, by John Kosner and Ed Desser, June 6th, 2022

The sports media industry is evolving, as streaming platforms begin to occupy beachfront once exclusive to linear TV. This is the first material platform change since cable arrived over 40 years ago. So where does this evolution stand, and what does it portend for the future?

First, let’s recognize what has not changed. Despite the decade-loss of 30 million subscribers, traditional linear networks continue to own the key rights for all major U.S. sports properties. Back to the future, a growing 18 million homes get top events ranging from four NFL games/week to the NBA Finals, World Series, Olympics, and PGA Tour, via a $15 antenna.

However, much has actually changed. Three of the four major pro leagues have made significant streaming moves. The bellwether NFL has sold Thursday Night (albeit its lowest-profile package) exclusively to Amazon. Recent MLB and NHL deals have included new streaming rights with AppleTV+, Peacock, YouTube, ESPN+, and Turner. Every major international soccer package (and perhaps soon, most MLS) is provided via streaming. Sinclair is planning a direct-to-consumer version of its RSNs, and half of the UFC is on ESPN+. Thus ESPN+, Peacock, and Amazon are already must-haves for big UFC, NHL, NFL, and soccer fans, in addition to cable.

Recently, streaming’s seeming inevitability hit a speed bump: Netflix actually lost subscribers … and half of its market cap. Suddenly all entertainment companies were under scrutiny. The vaunted NFL may license Sunday Ticket to a streamer, Apple, Amazon, or ESPN+, but it hasn’t happened yet. Has the pendulum started swinging back to traditional TV?

Far from it.

The traditional one-size-fits-all bundle of linear channels to 90% of U.S. homes is gone. The broadcast networks have lost 95% of their adult 18-49 average prime-time entertainment ratings over the past four decades. Today, “prime time” more aptly describes each of Amazon and Netflix’s ~75 million U.S. subscriber universes and even the 95% of 18-29-year-olds who use YouTube; indeed, consumers love streaming (3+ hours/day!). Undifferentiated, all-you-can-eat linear programming buffets are giving way to more targeted, optional packages, all with much better navigation and curation, with or without ads and/or sports, and priced depending on ads, number of streams, or resolution quality. Sports are no longer a required buy for all pay-TV viewers. For sports fans, however, discovery of what you want has become much harder (good luck figuring where) with an average viewer now using seven different video sources!

Major rights packages including the Big Ten, NASCAR, Big 12, Pac-12, and NBA are soon coming to market. Will prior packaging persist, or will the shift to streaming continue? Yes!

Despite losing substantial reach, and more of their audiences, linear networks remain the primary gathering place for live sports. The sports industrial complex retains the experience, know-how, relationships and affiliate and ad revenue streams. Most important, the incumbents need to remain heavily invested in sports. Yet, each of them (except Fox) is also investing heavily in streaming. ESPN+, Paramount+, Peacock, and HBO Max are all in growth mode. They require marquee, monthly, differentiated content like sports to drive and retain paying subscribers.

Digital giants like Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google don’t necessarily need sports yet. However, commoditization is contributing to rising churn for all streamers. Every app is basically the same: an endless stream of horizontal tiles. It’s harder to distinguish any particular on-demand entertainment content, especially when so much is already free on YouTube and TikTok. Sports is the only genre that drives passionate audience day-and-date “tune-in” nightly at scale. And as leading streamers including Netflix are now embracing advertising, nothing tops sports.

Looking forward, we anticipate that streamers will return to favor — especially those buoyed by sports. That will trigger further growth in sports rights, powered by bigger streaming allocations.

We expect other changes, too. With fast-shrinking pay-TV plus slow-growing OTA-only homes, about 90 million today have sports access to the premier events. That leaves a rising 30 million outside the main sports ecosystem, without linear TV! Streaming better serves the 100+ million broadband homes — so look for leagues to further embrace that growing medium.

Also, just 34% of 18-29 fans buy network packages. These millennials spend just 20% of their entertainment screen time on TV, compared with 52% for baby boomers, and are far less interested in entire games.

Streaming-influenced changes in games packages are also on the way. Live, full-length games will continue to be offered, in more ways (ManningCast, BradyCast?), but there will also be a multitude of new sports formats targeted at different fan interests. Real-time “Red Zone”-like offerings of portions of games, heavier use and distribution of customized highlights, and integration of live events with gaming, social media, commerce, gambling, and NFTs will continue to change the game-viewing experience. Whoever succeeds in enhancing discovery for live sports viewing will have a true business breakthrough.

When we started at the NBA, the ultimate prize was a big broadcast TV package, with prime-time games, which automatically delivered massive audiences. Viewing is now splintered, but sports always cuts through. We expect more platforms embracing sports to attract (“lift”) and retain subscribers (as cable has done for decades). But, for now, the traditional sports media players will leverage their leadership continuity, albeit at thinner margins, as they build streaming businesses. Like the victors of the NBA and NHL finals series, it will take an extraordinary effort to win.

Ed Desser is an expert witness and president of Desser Sports Media Inc. (www.desser.tv). John Kosner is president of Kosner Media (www.kosnermedia.com). Together, assisted by Neil McDonald, they developed league strategy and ran the NBA’s electronic media operation in the 1980s and ’90s.

"How should smaller properties cope with the shrinking sports media pie?" John Kosner's latest SBJ column with Ed Desser

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, by John Kosner and Ed Desser, April 18th, 2022

By now, most are aware of cord-cutting, streaming growth, and the related tectonic changes hitting the sports media industry. Elite properties like the NFL, NBA, and “Power” college conferences will remain strong draws for the traditional sports TV players, as well as the new tech ones — earning continued exposure and rights fees. But in an era of diminishing pay TV revenue where bigger players, especially the NFL, are taking a far greater share of the shrinking pie, how do small and midsized sports compete in this new normal?

Let’s start by recapping the score:

NBC has shut down NBCSN, reducing linear shelf space;

The entire RSN business is in danger of collapse;

The remaining national sports cable networks have been losing 1-2 million subscribers per year;

Pay TV affiliate revenue increases are only barely keeping up, and most all of that goes to support the major sports; and

Network broadcast prime-time adult entertainment audience ratings are disappearing: down 93% over the last four decades.

What to do?

I. Prepare.

Don’t leave your sports media negotiations to the exclusive negotiation period. Properties should be doing long-term scenario planning, considering options, looking at adjustments, and rethinking their business models. One can’t expect double-digit growth to continue uninterrupted without meticulous preparation. Know your agreement(s), when they end, and project what the world may look like at that time.

II. Be Flexible.

Just being on a national sports cable network is not the end all be all anymore. Reach is down. Not only are these networks’ average viewing much smaller but so is the effectiveness of any promotion from them that you’ve been promised. Paying a network for airtime, only to have them fail to deliver a sizable audience — or worse still, rely solely on you to do so — is wasteful. Consider all the alternatives.

Viewing is increasingly fragmented. Streaming is ascendant; it’s how more and more audiences expect to find most content. Emerging talent like Pat McAfee at FanDuel and properties like Barstool and Overtime have scored significant viewership and attention operating off the pay TV grid. But while there is no barrier to entry, streaming comes with significant fixed costs, and heavy reliance on the host property to market, sell, and produce. You can go it alone, or partner with a streaming partner to save some of those hassles — but if you’re on another’s platform you give up the benefit of direct business relationship with your fan base … a huge incentive to pursue direct-to-consumer (DTC) to begin with. Research is necessary to estimate buy rates, packaging options, and pricing. Unlike being on cable, streaming is hardly turnkey.

III. Think the Way the Potential Buyers of Your Sport (Networks and Fans) Do.

When we started working together at the NBA four decades ago, NBA Finals games aired on late-night tape delay. In fact, the NBA drew lower audiences than horse racing, boxing and bowling. Our NBA was certainly not today’s global juggernaut. Our league office colleagues and teams had to think differently — and we did. We started literally by itemizing our media “assets” and assessing how they were and should be utilized. Rick Welts, then the president of NBA Properties, created compelling decks (using actual slides!) that helped us create and then refine our narrative.

Ask yourself a bunch of questions:

What is “the story” of your sport? Do you have a tight version of that ready to present in multiple forms of media?

How well do you understand your community of fans? Are you able to marshal them?

Are you willing to take chances (“do anything”) to distinguish your product? If so, how and how much?

Are you investing in storytelling, including and especially from your athletes, to get audiences outside your core to care? It’s now part of lore that F1 commissioned “Formula 1: Drive to Survive” on Netflix and now its ratings have exploded on ESPN. The truth is it’s easier for small properties to take fans behind the curtain — there’s less to lose.

Do you have a real-time data feed available for your events — key to data and betting company deals and fan fantasy and wagering?

Do you have your own updated “assets” list?

It’s all less risky than you might think. Failure to take chances probably places you further behind the juggernauts, and the new sports audiences relish (and now expect) customization, curation and behind-the-scenes access (live and on demand). Accommodate their preferences!

IV. In This Quest, Technology is Your Friend.

You don’t need an army to appear to have one. Sophisticated sports artificial intelligence startups can create and instantly distribute personalized sports video highlights to all leading social media networks simultaneously. Others can identify your social media audiences and your super users who spike awareness for your sport. Need to add real-time interactivity to your app? There are partners for that. Best of all, these startup companies compete themselves and are hungry to build businesses like yours to be able to tell their success stories too.

In this world of Goliaths and infinite choice, nothing comes easy for small to midsize sports properties. Nonetheless, these exercises we are suggesting can be both exhilarating and lucrative. Start this necessary work today!

Ed Desser is an industry expert witness and president of Desser Media Inc. (www.desser.tv). John Kosner is president of Kosner Media (www.kosnermedia.com), a digital media expert and sports startup investor. Together they developed league strategy and ran the NBA’s electronic media operation in the ’80s and ’90s

John Kosner is quoted about the media value of the Women's NCAA Women's Gymnastics Championship in the Wall Street Journal

Original Article: Wall Street Journal, by Louise Radnofsky, April 13th, 2022

AUBURN, Ala.—Hours before the biggest college basketball game of the year, Auburn’s basketball arena felt like the loudest place on earth. The roaring wasn’t for basketball. Women decked out in orange, families with young children, couples, older men and students were all screaming for the Tigers at a college gymnastics meet.

“This is our first time,” said Lori Wilson, who flew in from Lakewood, Fla., and said she was loving it. “Our boys’ fraternity is having a moms’ weekend and we were looking for something to do,” she said. Her son and his fraternity brothers were watching in another part of the arena.

It’s been dubbed “The Suni Effect”: a megawatt moment for women’s college gymnastics brought about by the change in NCA A endorsement rules. For the first time, Olympic gold medalists can compete for a college team without forfeiting lucrative professional opportunities—including the reigning all-around champion Sunisa Lee, who has spent much of her busy freshman year marketing herself and her sport.

This golden hour is emerging around the country, but probably nowhere as intensely as at Auburn, as Lee and her college team advanced from the NCAA regional round their school was hosting. The Tigers’ performance propelled the team to the national championships in Fort Worth, Texas, where they will compete in a semifinal Thursday. The title will be awarded Saturday.

The reaction to Lee getting a “perfect 10” on the balance beam was enough to endanger tender eardrums. But so was the shouting when her teammates, Derrian Gobourne and Drew Watson, performed on floor and vault, respectively. The crowd of 6,166 bellowed: “It’s great to be an Auburn Tiger.”

By most metrics, it is. The school says it sold out every regular meet this season. The average price of an Auburn women’s gymnastics ticket sold through online ticket marketplace Vivid Seats from January to March 2022 was $53, up from $29 in 2020, the company said. Around 26% of the Auburn athletics tickets sold on the secondary market during that time were for women’s gymnastics. Just over 16% of tickets were for men’s basketball, in which Auburn rose to the No. 1 AP ranking for the first time in program history this season.

Gymnastics draws a diverse, majority-female audience desirable to many marketers for their household spending power. And Auburn has lines of small children waiting by the Charles Barkley statue outside the arena—not to pose by the legendary basketball alumnus, but for Auburn gymnasts to sign their posters and take pictures with them.

But it’s equally capable of drawing the football team. Tight end Micah Riley-Ducker said he goes whenever the team is competing at home, and at the regional event, was paying close attention. Had he ever seen gymnastics before? “Not until I got here and met them.”

There’s also enough interest for a restaurant here to put a different regional gymnastics round on one television screen, and Duke-UNC’s national semifinal in the basketball championship on the other.

None of this should be surprising. Women’s gymnastics is the marquee event of the Summer Olympics, even after revelations of the physical dangers and abuse for many of the athletes. NBC says that as many as 18.9 million saw Lee take the all-around title in Tokyo on television alone.

The college version of the sport is, in many ways, more comfortable viewing. Its gymnasts have leotards that are often more fun, with more exciting hair and an attitude that is almost breezy when contrasted with elite gymnasts. College floor routines have better music and more personality, many of them built to go viral. The skills are slightly reduced, but performances typically look more secure. And there’s the prospect of rooting for a school.

“I just like the whole collegiate thing,” said Roger Riley, an electrician attending the regional meet with his wife Shannon, a preschool teacher and longtime Auburn fan. “And I like the floor routines. They can be themselves.”

It wasn’t always this way. Auburn and other gymnastics powerhouses like Utah, LSU, Alabama and Florida can pack their arenas now, but it took years. Many of those coaches credit the SEC Network for televising meets since 2014, with the “Friday Night Heights” franchise. The SEC, for its part, credits the coaches with a P.T. Barnum-like approach to staging a meet.

SEC associate commissioner Tiffany Daniels said that the popularity “has also made ESPN more bullish about wanting to show more gymnastics.” ESPN, meanwhile, has worked with coaches to create a more viewer-friendly “final four” format in recent years than past championships, which involved six teams in a hard-to-follow rotation.

“It streamlined our championship and made it extremely fan- and TV-friendly,” said D-D Breaux, the LSU head coach for 43 years who retired in 2020. It made scoring easier to understand, she said. It also made it possible to create a bracket.

The women’s 2021 national championship, when aired for the first time on ABC, drew 808,000 viewers for an unprecedented Michigan victory that gave gymnastics its own claim to spring upsets. The 2022 final will be on ABC again.

Capitalizing on this success will be difficult for the NCAA, however, for the same reasons that are pinching the increasingly popular NCAA women’s basketball tournament. Media rights and corporate sponsorship deals for the events are captive to long-term deals that undervalue them.

The NCAA’s TV deal for the gymnastics championship has long been part of a package—for rights to 29 championships that aren’t men’s basketball—that ESPN currently pays about $34 million a year for.

At the same time, potential sponsors of the women’s gymnastics championship have to go through CBS and Turner, the broadcaster of the men’s basketball tournament, in a separate deal that runs through 2032. The arrangement erects a barrier to companies that might not be interested in sponsoring men’s basketball but see a different, valuable proposition in women’s gymnastics.

The lack of revenue dedicated specifically to sports like women’s gymnastics allows the NCAA to say, for example, that they lose money on the championships. This includes the pandemic-staged version in 2021, for which the organization declined to quantify the loss, and 2019, the first with the “final four” format, which the NCAA said was around $400,000 short of breaking even.

An analysis commissioned by the NCAA to examine gender inequities in its championships found that the arrangement significantly undervalued events like the women’s basketball tournament. Consultants Ed Desser and John Kosner, who worked on the report, said the tournament could be worth $100 million a year in media-rights fees alone starting in 2025 after the current deal ends.

It isn’t clear what the potential value for the gymnastics championship would be, but it’s clearly more than it is now. ABC also aired the first-ever regular season meet on broadcast TV this year, Alabama-Florida, drawing 624,000 viewers. ESPN and ABC are both owned by Walt Disney Co.

“ESPN is upgrading gymnastics to windows on ABC not because it’s benevolent,” said Kosner, who was previously ESPN’s head of digital media. “They can see and hear the interest.”

If the package were broken up, Kosner said, it could also create more competition for the rights. “The original package was designed in a way that ESPN was practically the only entity that could broadcast all these championships,” he said. “If you don’t create a package that only one bidder could handle, you’re going to get more bidders.”

The sponsorship arrangement could also be revised, said Desser, a former NBA executive. “If you’re willing to get your hands dirty, it’s all doable.”

The NCAA said it would explore options to grow all championships at an unspecified later date. It confirmed that businesses currently have to go through the NCAA Corporate Champion and Partner Program, and that plans to change are among the long-term recommendations from the gender equity review that the association is still considering.

For schools and coaches, however, the moment is here already.

Marcy Girton, the chief operating officer for the Auburn athletic department, says the school has drawn interest from fashion, apparel, cosmetics and beauty product brands about becoming a sponsor or advertising at meets next season.

“If you look at our attendance rates across the country, they’re going up. Viewing rates have been going up. And then the Olympians coming in,” said Jeff Graba, Auburn’s head coach. “It’s a great time. It just shows what’s possible in this sport.”

Write to Louise Radnofsky at louise.radnofsky@wsj.com

"The End of All or Nothing" in Sports Media, John Kosner's latest SBJ column with Ed Desser

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, by John Kosner and Ed Desser, February 21st, 2022

For the four decades of the cable sports era, the choice for fans has been simple: Buy cable/satellite and get everything. Every major national or local sports event, on all widely distributed channels, plus every major entertainment, music, and news network. In short and until recently, substantially all programming — an all-you-can-eat buffet (except movie channels) — at a set per-home price. Or, should you decline to buy pay TV, you get nearly nothing (just broadcast if you were enterprising enough to put up an antenna). Netflix now is obviously an outlier, but virtually all of the sports events you would be likely to watch were part of “the bundle.”

This ultra-simple way of buying and consuming live sports is already coming to an end. This fall, you’ll need Amazon Prime to see most Thursday night NFL games. You must have ESPN+ if you’re a UFC fan. As our friends at “The Marchand and Ourand Sports Media Podcast” pointed out, tennis fans had to pay twice (ESPN and ESPN+) to watch all of the Australian Open matches. That’s the new fan playbook, and it’s more expensive. Soon it’s rumored that Apple TV+ may be required to watch Wednesday night MLB games previously on ESPN. If you want RSNs, forget about Hulu or YouTube TV, and if you are a big sports viewer, ignore Dish altogether. The great unbundling is underway, and it is truly the end of “all or nothing.” That won’t happen all at once, but the change is coming this decade. And that’s before more seismic effects wrought by everyone from FanDuel to Discord to Fanatics.

How should sports properties navigate this transition? We have four main observations:

1. The future of distribution is fragmented — and soon to be further split among linear TV, streaming (and PPV of various durations), betting, social media, chat, and 3D interactive platforms. Ten years ago, you could reach substantially your entire audience through a single deal with one sports media company. That is no longer true, especially for younger viewers (see No. 4). Traditional “exclusivity” in media deals needs to be fundamentally reconceived — establishing greater value in more narrow grants than just cable or broadcast, first half or second half of the season or by language, geography, or night of the week, which were all that was needed pre-internet, in a simpler time when distribution channels and business models were far more limited. Thus:

2. New licensable products and formats are crucial. The single vanilla live game broadcast production (another all-or-nothing relic) is not nearly enough anymore either. Multicasts will proliferate: The ManningCast and the Nickelodeon NFL Kidscast are just the start but expect more of these targeting multiple demographics/languages from rights holders, not just rights buyers. There will be video highlights in multiple forms and lengths, increasingly personalized and curated “FAST” (Free Advertising Supported Television) channels, imaginative “re-watches,” immersive 3D interactive experiences (Sport@Roblox), betting, 4/8K, merch, and NFTs. To do that:

3. A sports property needs to become its own executive producer — in terms of audience segmentation, game presentation, formatting storytelling, strategic scheduling, and investment. Much is rightly made of the NFL’s recent blockbuster 11-year, $113 billion TV rights deals. Behind the scenes, the NFL earned the agreements by consistently increasing the value of its product for fans and media partners — pioneering the Red Zone, extending the regular season, expanding the playoffs (Super Wild Card Weekend), moving the Super Bowl and NFL draft back, creating the Rookie Combine, defining a window for free agency and making its training camps an event. The NBA and its players have achieved leading global reach on multiple social media platforms, and have invested in and accelerated interesting tech startups. The lesson for all: You can’t just rely on the network “professionals” anymore. “Who is our executive producer?” our former boss NBA Commissioner David Stern used to challenge us (Ed was the NBA’s first back in 1982). The NBA just filled that position again, naming our former colleague Gregg Winik, whose assignment is imperative because …

4. Younger sports fans are much different. The iPhone debuted in 2007, and it changed almost everything about experiencing sports. Now, fans have in their pockets: the live game broadcast (soon, multiple versions thereof); every score, 24/7 breaking news; unlimited social media feeds, alerts, stats; the ability to transact, bet and buy instantaneously, anywhere. On Jan. 31, the NBA put “CrunchTime,” its version of RedZone, exclusively on its own app, commercial-free. In 2027, this iPhone generation will turn 20, just entering their buying-power years. Are you ready for that?

The end of “all or nothing” is thus quite daunting. Sports are no longer the default source of intergenerational bonding. We can’t assume our kids just want to “go out and play” and automatically share the Little League, pickup basketball, or touch football matches that were the experience of older fans and fed traditional sports fandom, parenthood, and viewership. We also don’t know when we will finally have COVID under control and what its long-term impact is on sports. However, unbundling and new tech breakthroughs also bring opportunity (plus, of course, the promise of multiple new bundles to come). Sports properties like the NFL and NBA that go on offense now will likely be rewarded.

Ed Desser is an industry expert witness and president of Desser Media Inc. (www.desser.tv), which has advised on over $30 billion in sports/media transactions. John Kosner is president of Kosner Media (www.kosnermedia.com), a digital media expert and sports investor. Together they developed league strategy and ran the NBA’s electronic media operation in the 1980s and ’90s.

John Kosner is Quoted About his Late Colleague Tony Pace in the Sports Business Journal

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, February 10th, 2022

Former Subway CMO Tony Pace dies in snowmobile accident

Former Subway CMO TONY PACE died on Tuesday in a snowmobile accident near Big Sky, Mont., after he "struck a tree and went into cardiac arrest," according to Jack Neff of AD AGE. He left Subway in '15 after "nearly a decade" with the restaurant chain. While there, he "built the brand’s value," as tracked by Millward Brown’s annual Brand Z assessment, from unranked to No. 40, with a brand value of $22B, according to MASB. Previously, as an exec at Young & Rubicam and McCann-Erickson, he worked on such brands as Kentucky Fried Chicken, Coca-Cola and Capital One. Pace concluded a two-year term as Chair of the ANA in '16, among "other things overseeing the group’s probe into media transparency issues." Pace in '17 became CEO of MASB, a group "working toward developing standards for objectively evaluating brand value and the contribution of advertising to them" (ADAGE.com, 2/9). Pace's handprints were all over the sports space, including negotiating Super Bowl ad deals, CARL EDWARDS' NASCAR deal and Subway's pact with CLAYTON KERSHAW, among others. Subway in '11 won the Sports Business Award for Sponsor of the Year, with Pace accepting the award (SBJ). Former ESPN exec John Kosner tweeted that Pace was a "quiet MVP" in the growth of ESPN Digital because he was always "aggressively supporting" their programs and platforms, including the pursuit of BILL SIMMONS (TWITTER.com, 2/9).

John Kosner Spoke About the NCAA Gender Equity Media Study at the SBJ Media Innovators Conference in NYC on Nov. 9

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, November 9th, 2021

Sports media – and the media world as a whole – is undergoing a seismic shift. Mega-mergers and divestitures are making headlines. OTT services are reshaping programming and distribution as consumers migrate away from legacy media. RSN models are under fire. And sports betting is adding an uncharted element to the North American market and opportunities for media companies and the gaming industry. On November 9th and 10th, these issues and many more will be examined at Sports Business Journal’s Media Innovators conference. Stakeholders from across the emerging media landscape will discuss the day-to-day challenges they are facing, opportunities they are recognizing, and the long-term planning that will keep them competitive in an ever-changing marketplace.

John Kosner & Ed Desser Featured in SBJ Piece on NCAA Gender Equity Media Study

Original Article: Sports Business Journal, by John Ourand, November 8th, 2021

Consultants Ed Desser and John Kosner said the NCAA women’s basketball tournament should be worth between $81 million and $112 million per year. Former NBA executive Ed Desser, who now runs a sports media consulting company, was sitting in his California office earlier this year…

John Kosner Spoke About MegaCasts with Michael McCarthy of Front Office Sports

Original Article: Front Office Sports, by Michael McCarthy, November 3rd, 2021

Heads up, NFL. The NBA is ordering up more alternate game telecasts similar to Omaha Productions’ popular ManningCast with Peyton Manning and Eli Manning.

The league is expected to announce an alternate telecast co-starring Jamal Crawford and Quentin Richardson for NBA League Pass, its subscription-based product that provides access to hundreds of live and on-demand games.

Starting Thursday, Crawford and Richardson are expected to provide their own weekly commentary for the next 10 weeks.